McDonald’s Milkshakes Are Weak. Brand Is Why I Buy Like 6 a Year.

Twice now, my family and I have spent winter weekends at a local Hyatt Hotel in Oak Brook, Illinois. It’s a sprawling old building hidden in the woods with a pool large enough for the antic gangs of small kids. Its primary function, it seems to me, is to host emergency mini-staycations for local families locked in the dark nadir of Midwest winter madness. (It’s great here! "Come and play with us, Danny. Forever... and ever... and ever.")

What actually makes the hotel remarkable, though, are the odd, light and consistent touches of McDonald’s fast-food restaurant branding throughout the building. Every painting on the walls in the hallways and rooms—and I mean every painting—bears some brand code (covert or overt); such as a faint pair of golden arches rising from a bucolic pasture, or an overly stylized Hamburglar-esque character taunting a fox for some reason. You’ll find the McDonald’s logo imprinted on bathroom doorknobs.

Thanks for reading AD SUPERA | Lane Talbot! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Imagine The Overlook Hotel from The Shining with a subtle fast-food theme. Until 2018, this hotel had been associated with the adjacent McDonald’s corporate headquarters property. The McDonald’s Corporation vacated but the brand’s bright fingerprints remain.

On our last visit, when my kids and I left the room for the pool, we found ourselves walking along with one of the hotel managers. I asked him, “Is it just me or does this hotel still smell like a McDonald’s?” He did not deny that it did.

The building, really, is a monument to McDonald’s brand codes.

As am I.

I remember—vividly—the faint vinyl smell of the McNuggets toys and I always will. I can very nearly filter the world through the soft-warm color scheme of the late 80s McDonaldland television commercials at will. I paid real dollars to rent the physical video games (There was more than one.) from Blockbuster.

The McDonaldland advertising campaigns captured me wholly. I don’t eat McDonald’s anymore [he says a little too loudly], unless you count the milkshakes I’ll grab at a drive-through two, three, or half a dozen times a summer.

The point isn’t that I’m a hypocrite. The point is that I’m a light category buyer, and I will be forever.

Why? Because some sharp creatives won the battle for my childhood imagination and the brand has kept its foot on the pedal ever since. The result: I’m still spending money at McDonald’s today, even and often when I know I have much better options.

As Byron Sharp writes in How Brands Grow, “Advertising works largely by refreshing, and occasionally building, memory structure. Marketers need to research these memory structures and ensure that their advertising refreshes these structures by consistently using the brand’s distinctive assets.”

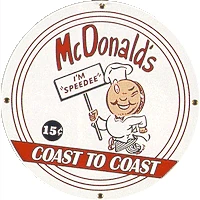

McDonald’s had distinctive assets—like a brand mascot—before they had indoor seating.

"Speedee" wasn’t so much a character as a glyph. Speedee predates Roy Kroc, who infamously separated the McDonald brothers from their enterprise.

It was Kroc who possessed the instincts to slap a striking brand character on television to win the attention and favor of the kids. The Ronald McDonald character was introduced in television commercials in 1963. Ronald, at first anyway, looked like a clown who made his own costume 10 seconds before showtime.

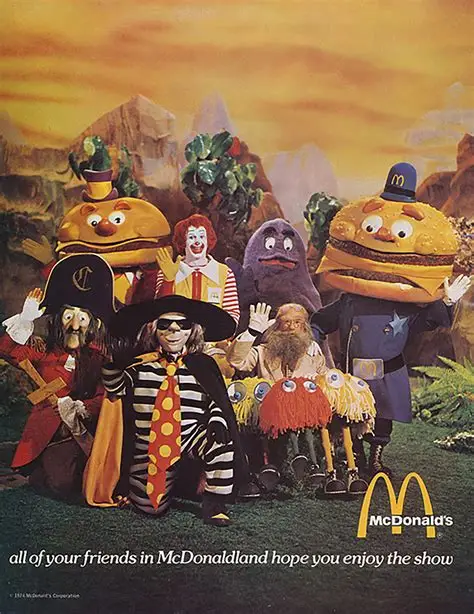

The McDonald’s brand steered directly toward children by aping the characters and cartoon worlds vividly portrayed across breakfast cereal boxes and commercials at the time. Chicago ad agency Needham, Harper & Steers expanded Ronald’s world with a cast of new brand characters that fit the bill.

In 1971, “McDonaldland”, the hyper color-saturated paracosm, arrived fully formed and bursting with surreal and wacky landscapes, talking trees, bumbling and threatless villains. It looked and sounded no different than any number of the era’s children’s television shows. (This would soon become a significant legal problem.)

McDonaldland was the vehicle the brand used to storm American childhood, which then played out in the shared mental landscape of television.

Does it sound silly? Does it sound predatory? Somewhere in the middle? Regardless, it’s effective. Emotional connection, brand storytelling, character marketing. They work. That’s why McDonald’s kept up the pressure.

The cast expanded further in the 80s. Birdie the Early Bird arrived in 1981. (Odd choice to use a bird character to sell eggs and chicken, right?) The McNugget Buddies arrived soon afterward. Followed by CosMc the alien. McDonaldland arguably achieved critical mass in the late 80s (when I was conscious enough to notice).

Videogames and a direct-to-video movie “The Adventures of Ronald McDonald: McTreasure Island” exist!

(I considered watching the full thing in advance of writing this but I have a job, kids and a life—next time, baby.)

Who was McDonald’s targeting with all this brand activity?

Every single child with ears to hear and eyes to see. I wasn’t in the marketers’ offices, but I was their audience. I absorbed—consistently, over years—the brand's heavy broadside attack.

What we experienced was always-on and aggressively creative brand advertising that captured attention, created iron-strong memories that still fire regularly today when I'm hot, need a sugar fix, and know I have better options.

And just like that, I am separated from a few bucks, a couple times a year.

It will never stop. McSuccess.

Such brand activity (characters, worlds, silly dramas) only works on children, right?

Adults are no less susceptible. Categories like insurance, travel and household cleaning products are thick with brand characters. Many of whom intersect and interact. Progressive has built their own MCU of personalities.

McDonald's found success using the tactic against adults in the mid 80s. Seeking to improve their dinner traffic, they did what too few brands do when addressing a specific challenge. They got weird, I mean, distinct—and they did it with color and volume.

Enter Mac Tonight.

The new brand character was a lanky lounge singer with a weapon of a crescent moon for a head. Mac—played by former mime Doug Jones (The Shape of Water, Hellboy)—sang a McDonalized rework of “Mack the Knife” in a series of surreal ads that linked the restaurant with late night eating.

Launched in California in late 1986, the campaign went national by August 1987, and global by 1988.

Mac Tonight drove up to a 10% increase in dinner sales within California, a 2x lift in ad recall after the national launch, and higher recognition than the contemporaneous New Coke campaign.

Mac addressed a clear business problem with creativity and distinctiveness. He was memorable, shareable, and everywhere (TV, merch, animatronics, even a Simpsons appearance).

So why didn't they run it forever?

Maybe they should have.

In 1989, Bobby Darin's estate filed a +$10M lawsuit over the musical likeness and McDonald's didn't fight it.

There's also an argument that this brand character may have orbited just a touch too far beyond the core McDonald's brand characters (with whom I don't believe he ever interacted). The primary campaign was retired. Over the years, Mac made a few rare showings until his final commercial appearance in 1997.

Mac Tonight was a big creative swing. Character, music, and–above all else–a striking and distinct visual that created lasting memorability. So, while he might look like the stuff of a fever dream, he was then and is now an admirable example of the application of creativity against a specific business problem.

Characters don’t only work on kids. Mac Tonight stood out, arrested attention, and then delivered relevant messaging so simple and clear you could read it from space.

(Heartbreaker: while reading up on this, I discovered that Mac's image has since—and bafflingly—been appropriated by hate groups because Internet. Major downer. But I believe my point on addressing a business problem with creativity still stands.)

By the early 2000s, McDonald's and other fast-food brands moved away from the paracosmic (I love using that word) and into a more modern, adult-focused, "healthier", lifestyle-oriented imagery and messaging.

Things change. National moods and conversations careen. The good-natured cartoon vibrancy of McDonaldland no longer fit with the new, elevated global image.

The 2001 Eric Schlosser book Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal and the 2004 documentary Supersize Me contributed to a hard demand for a responsible revision of fast-food marketing practices.

The characters that burned a hole in my memory had to go.

They're still serving their time in brand character jail now but they do occasionally get a brief release. See the very recent and outstanding Minecraft/McDonald's collaboration.

So, back to the milkshakes.

Do you know what the opposite of a food desert is? The western suburbs of Chicago.

The air we breathe here is threaded with giardiniera. We carry loose ground beef in our pockets for just in case. We wash our faces with pump cheese. Okay, I'll stop, but the point is if you want some food item here, you don't have to settle for McDonald's. I would argue that you shouldn't.

Go deep, go local. Get a sandwich from Johnnie's Beef in Elmwood Park. Fontano's Subs in Hinsdale. Tate's Ice Cream in La Grange. (By the way, I know it's crazy dangerous to write about food in Chicago. Give any strong opinion and the knives come out. People will call you a rookie, assume you live in Naperville, tell you to go back to St. Charles.)

I do go local. Mostly. But every once in a while, I do spin through the drive through and get that good-bad cheap stuff.

It's an emotional decision. It was engineered to be so.

Thanks for reading AD SUPERA | Lane Talbot! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.